IFS Institute : The Internal Family Systems Model Outline

« …So my understanding of how IFS works in practice is it identifies these almost little personalities in the brain. There are managers, who try to protect you from feeling unsafe (also called protectors), and the firefighters, who respond to moments of crisis, the exiles, who you’re trying to avoid, and that helps people identify these distinct parts of their personalities, and how those parts come out and contribute to different reactions.

And that seems like something that would be helpful even outside the context of therapy. In addition to all the wonderful qualities of mine you listed a minute ago, I do a lot of meditation. And one of the things that years of that is done has make me much more sceptical that there is just one of me in here. When you’re sitting there just watching your mind, the constant question is, well who thought that? Who thought thinking that would be a good idea? I didn’t want to be there.

And the mind has felt to me for a long time like it’s more of a corporation. You know, it has different divisions, and some of them have big budgets, and some small. But family systems seems to get at that too. That one thing that actually causes people frustration and shame is they are told they’re in control or should be in control of their minds.

And then it’s very frustrating, for me as somebody who has struggled a lot with anxiety and obsessive rumination, it’s very frustrating to not be able to control my own mind. Because that feels like I’m failing. And the idea that it’s actually not something I should be able to do, that it’s not just one singular mind, but a lot of different minds or something vying to be heard, there’s some relief in that. And it seems to me some real accuracy in it… »

Dr. Bessel van der Kolk on Internal Family Systems therapy

The Voices in Your Head

On the inside, we are more like a family than an individual.

“Please,” the teenager told me, “I can’t go back to therapy. I’m so tired.” She was intelligent, anxious, and depressed. “I’ve tried it, all the coping stuff. It’s so hard, and it makes me feel worse when I have to watch all my thoughts all the time. I can’t keep it up. I get obsessed with having to watch every thought.”

She was not the first person I had heard this from. Her therapy was not working for her, so I had a reasonable indication for medication. Still, I wondered if this bright, insightful, and artistic person was a candidate for a less commonly used therapy called IFS. When I told her about it, her face opened up, “Yeah, yeah, I’ll try that.”

What Is IFS?

When Dr. Richard Schwartz was a young psychologist trained in family systems, he found himself hitting the wall with some of his clients. Family systems is a theory which posits that our behaviors are related to our roles in our families and that the system determines a great deal. Change the system, change the person. But it was not working with his bulimic clients.

On the inside, we operate like a family system

Dr. Schwartz, now Adjunct Faculty, Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, simply started listening. He began to notice an interesting pattern,

“They started talking about these different parts of themselves, that’s the word they used. And they would talk about this critic who, when something bad happened in the outside world, would start to call them names. Then that would bring up another one who would feel bereft and empty, alone and hurt, and then to the rescue would come the binge. That would just take them out of their body and turn them into an unfeeling eating machine. But that would bring back the critic, who’s now calling them, in addition to all the other names ‘fat pig.’ Which brings back that empty alone one. And it just sounded to me as a family therapist like these sequences of escalating circular interaction that we were studying in families. So I became intrigued, and I began to try to track these sequences… And then I started noticing that I had them too.”

We all do this.

“Part of me wants to eat the cookie, but another part of me really wants to stick to my nutrition goals.”

“I’m sorry, I wasn’t myself when I said those things. That wasn’t me.”

“I’m torn.”

“I’m working on silencing my inner critic.”

While the idea of parts of the personality or sub-personalities have been explored by many others, the unique finding came when Dr. Schwartz noticed that the parts seemed to interact like a family. His training was now paying off, and he used some of the techniques he’d used to get family members talking to each other with his clients. Except this time, he had them talk to themselves on the inside.

Dr. Schwartz’s Internal Family Systems (IFS) model “represents a new synthesis of two paradigms. One of these is called the multiplicity of mind—the idea that we all contain many different beings. The other is known as systems thinking.” (Schwartz, 9) When I talked with Dr. Schwartz, he elaborated, “Falconer and I cover the idea that the mind is naturally multiple as it appears throughout the history of our culture and also the history psychotherapy, but also as it appears in different branches of sciences.” Indeed, a quick survey of recent neuroscience will show that the idea is prevalent.

The Parts

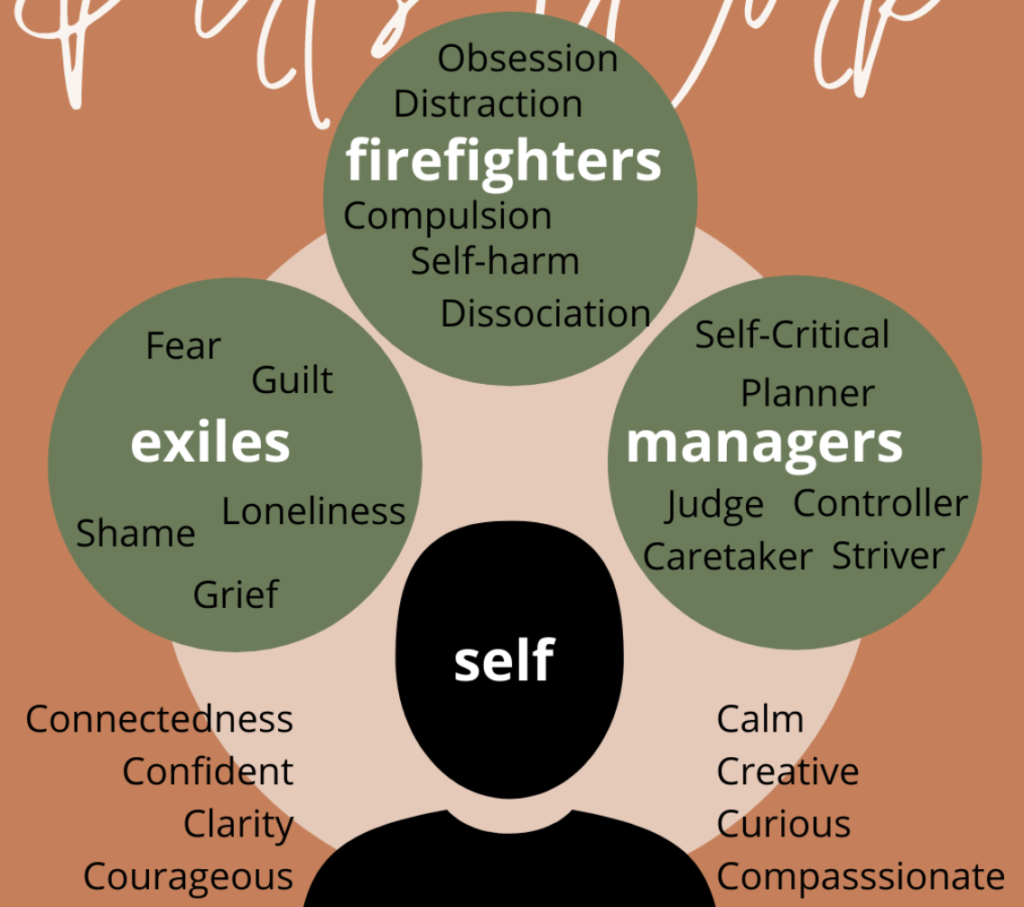

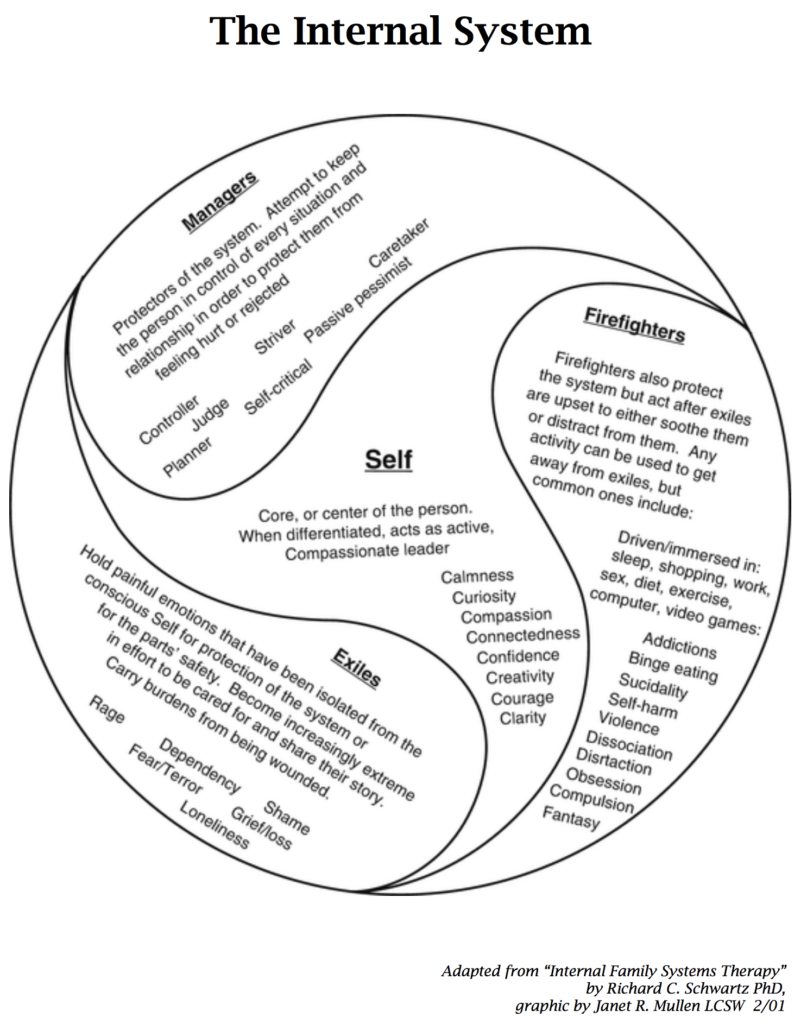

But it’s the systems part that is the most interesting. The idea is that we have three main types of parts, all of whom behave with good intentions: managers, exiles, and firefighters. These exist in relationships with each other that may be healthy or dysfunctional.

Exiles are the parts that hold our pain or shame, and they often originate in childhood. They take on our traumatic experiences to protect the most essential part of us, our true selves, but by doing this they can become stuck. The rest of the system exists to keep them quiet so that we don’t consciously experience our pain.

The managers are the responsible adults, who help us function as we are supposed to. In fact, as adults, most of us live primarily from one of our managers and think that’s who we really are. Managers make sure we interact with the world in a way that protects us from pain; they keep our exiles from showing up to flood us with emotion. But when they fail, the firefighters show up.

The firefighters use more extreme behaviors to distract us from the pain, whether acting out in anger, addictive behaviors, impulsive behaviors like binge eating, or more socially acceptable behaviors like overworking. Even though the firefighters seem to be prompting harmful behaviors, their good intention is to protect the system.

The Self

IFS has something very unique at the center of the model: the « Self » with a capital S (≈ » healthy adult » in schema/mode therapy | « wise mind » in DBT). “This idea that people have a self shows up in religion. We have the contemplative sides of religion, and every major religion talks about it the same way,” Dr. Schwartz explained.

« Facing Herself »

What is the self? It’s the core of us. To children, it’s often explained as “the real me.” When the parts feel safe enough to let it, a profound healing energy emerges in people that seems to know what they need. Far from being deficient and needing the help of the therapist, IFS posits that people are equipped with self already, and the goal is to access that self.

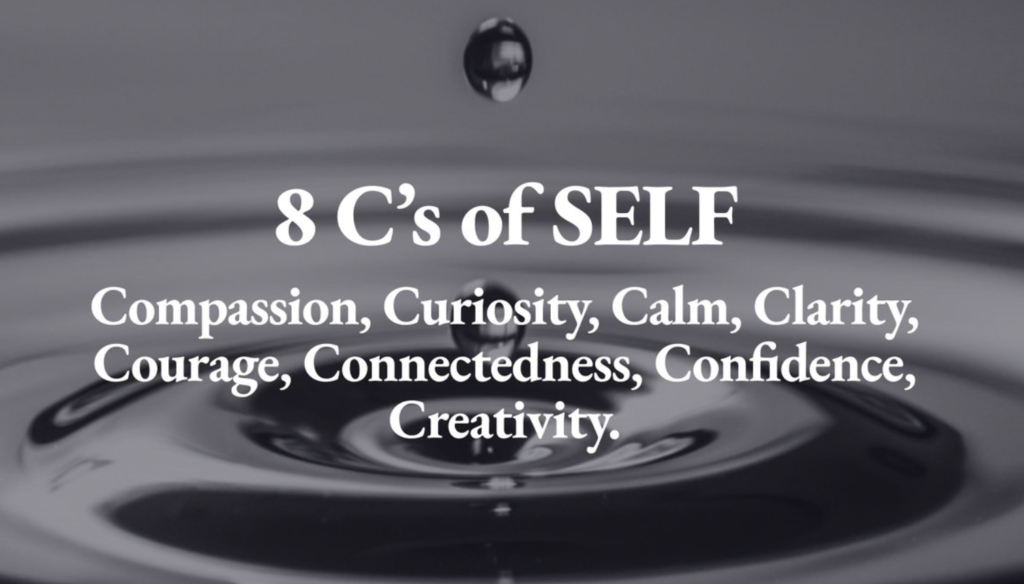

The self is noted to have a list of remarkable characteristics, including eight Cs and five Ps. The eight Cs are calmness, clarity, compassion, curiosity, confidence, courage, creativity, and connectedness. The five Ps are presence, patience, perspective, persistence, and playfulness.

So Schwartz is claiming that we all have an essentially ideal human inside of us already. While the self is the natural leader of the family, harmful incidents in the past created exiles and protectors who wrested control away. The goal of IFS therapy is to restore the internal family’s trust in the self, even as the pain of the past is healed by allowing the exiles to tell their stories and be freed from the burdens they carry. When the parts trust the self to lead, the internal family reorders itself in a healthy way.

Most of us don’t know we have a self.

“Do you think most people have access to their self?” I asked.

“No,” answered Dr. Schwartz, “that’s part of the problem. So it’s becoming aware that there is a self, but it’s covered over by these parts, and that self wants access. Self is your birthright. We work with kids down to age three, and they also have a self.”

I was curious, so I asked, “How can people start to access their self without a guide? Say they’re not working with a therapist?”

“It helps to know when you’re in self and when you’re not. We have a meditation that helps people get their parts in open space and then feel what it’s like to be in self. And then, the simple practice of just noticing how many of those eight Cs you are finding. And noticing how open your heart is, or noticing if you have a big agenda,” Dr. Schwartz shared. A big agenda would be a sure sign of a manager online.

Does IFS work?

IFS is listed as an evidence-based practice in the National Registry of Evidence-based Programs and Practices. Dr. Schwartz shared that a study on PTSD is to be submitted for publication. It looked at 13 clients with moderate to severe PTSD. After 16 weeks of IFS, only one person still qualified for a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder.

The young lady at the beginning (for privacy, a fictional case that reflects my true clinical experience) found that she thrived with IFS. It was a useful treatment modality for her, and her depression resolved without medication.

In his book « No bad parts » Richard Schwartz mentions the meditations by Loch Kelly

References

Dr. Schwartz, Richard C. (1995). Internal Family Systems Therapy. New York: The Guilford Press.–

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/shouldstorm/201906/the-voices-in-your-head